Building three apps in a single year was not something I planned. It happened gradually. One idea started as something I wanted to use myself; another came from seeing what people were already searching for; and the third grew out of noticing a small trend early and wanting to explore it properly.

What surprised me was not how different the apps were, but how differently they needed to be judged. That realisation changed how I think about building products and, more importantly, how attached I allow myself to get to any single idea.

Pushup Social and the cost of skipping validation

The first app I built that year was Pushup Social. It started as a fun idea for me and a few friends to compete in push-ups. Somewhere during the build, I convinced myself it could become much more than that. I started thinking of it as a breakout fitness product, perfectly timed and with a strong concept.

The problem was that I had done no real validation. I did not check keywords, I did not look at search demand, and I did not try to understand whether anyone outside my immediate circle was actually looking for something like this. I built it because I liked the idea and let that enthusiasm carry the project forward.

Even though the app looked small on the surface, it was not a small build. It needed authentication, push notifications, stats, a backend, and a clean interface to hold everything together. None of those things was complex in itself, but together they took time. In my case, that meant months of evenings.

When the app finally shipped, the outcome was fairly clear. Demand was low, downloads were low, and revenue followed the same pattern. That was not because the app itself was bad, but because hardly anyone was searching for this kind of thing in the first place.

It became the longest build of the three and, by most definitions, the biggest flop. At the time, that was frustrating. Looking back, it was useful. It showed me how easy it is to become attached to an idea simply because you have invested time in it, and how that attachment makes it harder to walk away when the signal is already there.

What changes when you start with real demand

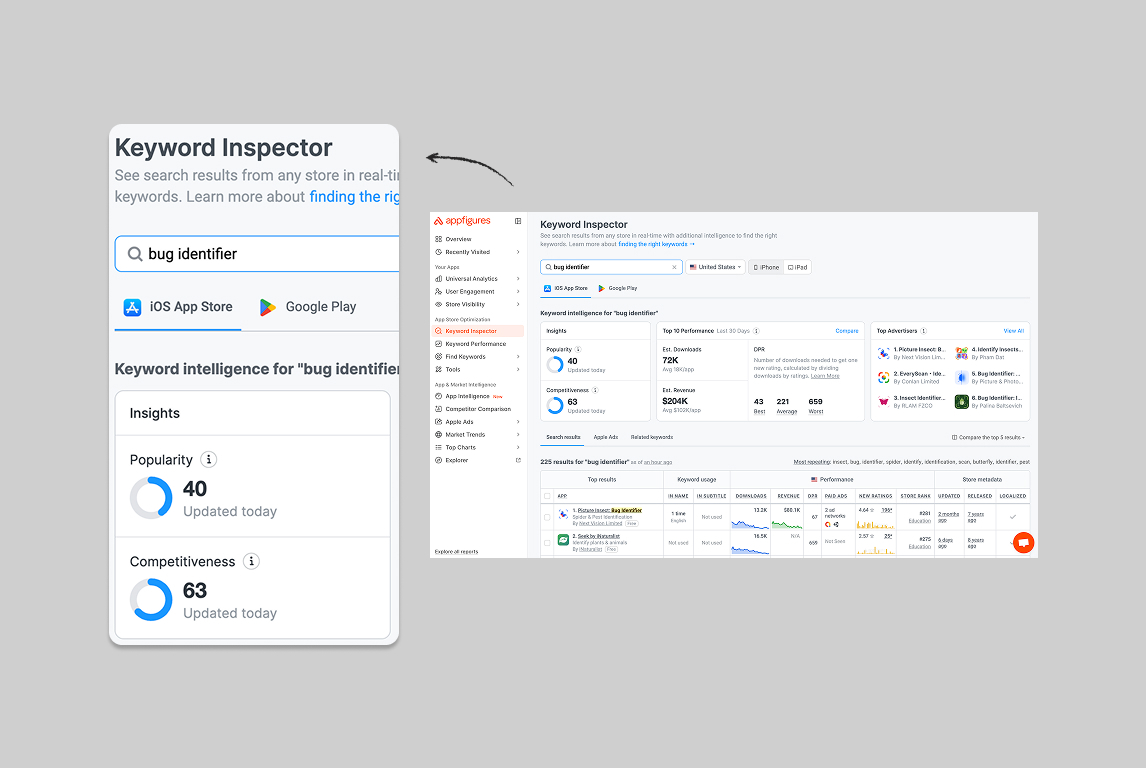

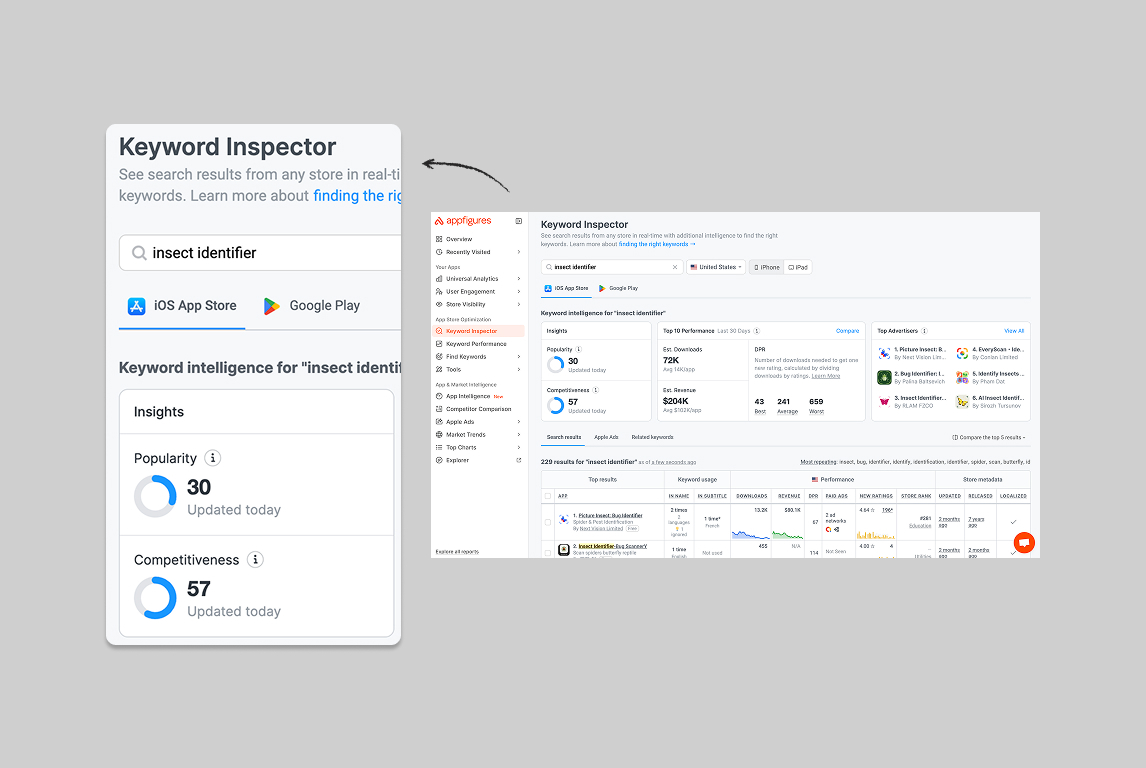

The second app I built was a much simpler utility tool. This time, the decision to build it came almost entirely from App Store keyword research. I was not aiming for a massive market, just one that clearly existed. For example, this is a keyword search for a bug identifier. You can see that the popularity of either is strong, but a single word change can increase its traffic.

There was no marketing behind it. All of its traffic came through search. Each month, it began generating around eighteen thousand impressions, twelve hundred downloads, and just under two thousand sessions. For a small, focused app with no promotion, that was enough of a signal to justify continuing.

Instead of assuming the app needed more features or a larger audience, I focused on how users were being asked to pay. Using RevenueCat, I ran a series of small, controlled paywall experiments.

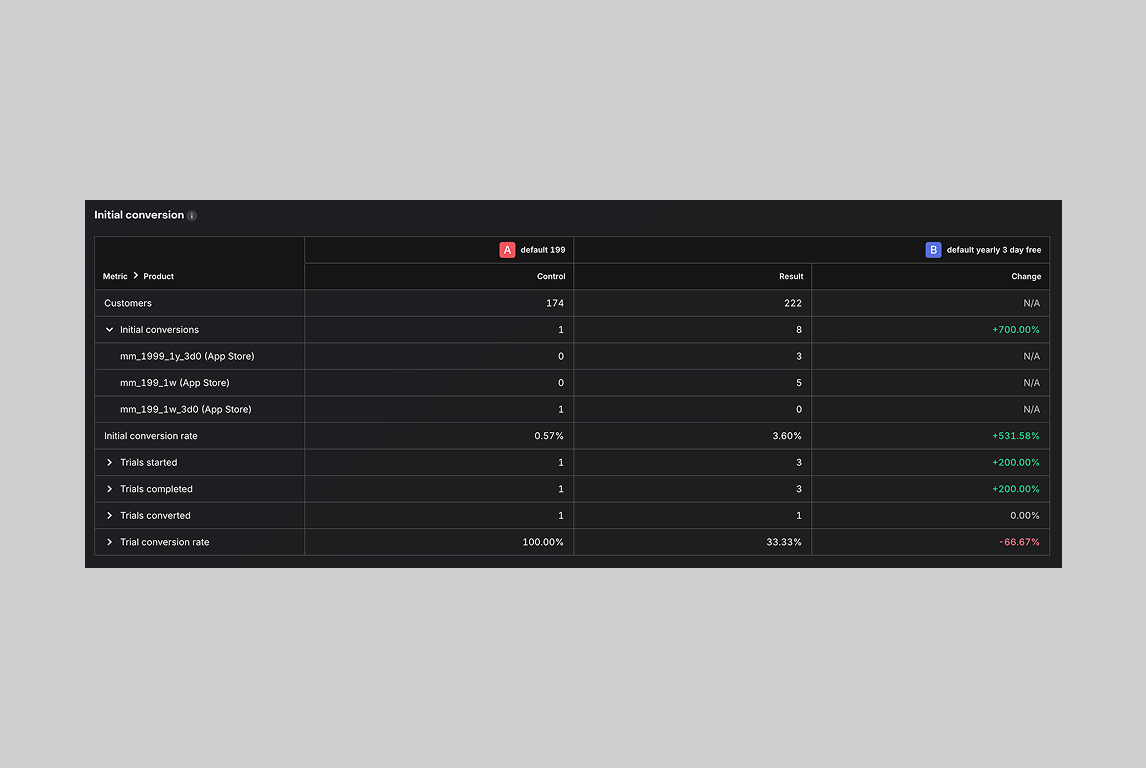

One experiment stood out in particular. In the first version, the weekly subscription included a three-day free trial, while the yearly option did not. In the second version, I removed the free trial from the weekly plan and added it to the yearly one instead. Nothing else changed. The app, traffic, and audience stayed exactly the same.

That single change produced a noticeable shift in behaviour. Conversion increased from 0.57% to 3.6%, with the number of users converting rising from one to eight over a similar period of traffic. Trials start, and completions follow the same pattern.

These were small numbers, but they were enough to show that the bottleneck was neither awareness nor product quality. It was how commitment was being framed. The app did not need saving or reimagining - it just needed testing.

Experimentation as the default approach

By the time I built the third app, I was already working differently. I checked demand early, shipped something simple, and assumed I would need to experiment rather than get everything right upfront.

This app sits somewhere between a utility and a creative tool. People understand what it does quickly, and it converts, but it doesn't feel finished yet. On a monthly basis, it generates around eight thousand seven hundred impressions, four hundred downloads, and six hundred and fifty sessions, all trending upward.

That was enough of a signal to keep iterating, but it also made it clear that acquisition was not the hardest problem. The more difficult work was deciding what actually belonged behind the paywall.

Giving too much away made the paid tier feel unnecessary. Locking too much made the app frustrating to use. The experiments here were less about pricing and more about features. I tested what stayed free, what became limited, and what felt reasonable to ask people to pay for. Some changes improved conversion and others did not, but each one removed a guess.

The app is converting well enough to justify continuing, but it is still very much in the phase of figuring out where users see real value.

Why flops stopped bothering me

Looking across all three apps, the common thread is not success or failure. It is that each one was an experiment, and each one eventually produced a clear enough signal to decide what to do next.

Pushup Social was a flop in the most straightforward sense. The right move there was not to keep pushing, but to stop. The second app worked because it started with real demand and was tested methodically. The third is still in progress, and that is fine too.

What changed for me was becoming comfortable with the idea that stopping is not a failure. In many cases, it is the outcome you are aiming for. The real risk is getting attached to an idea and dragging it forward long after it has stopped teaching you anything.

Treating apps as experiments only works if you are willing to let them end. Once I accepted that, building became faster, calmer, and far more productive. Some apps stick around, others disappear quietly, and both outcomes are acceptable.